|

19th Century Minstrelsy and Popular Entertainments |

|

|

19th Century Minstrelsy and Popular Entertainments |

|

Circuses

Gillies Burlesques |

|

Minstrel Shows first appeared within this context. They were variety entertainments based upon the imitation of African American plantation "types."

Daddy

Rice, also known as Jim Crow was the first to create a character

based upon an African American person. It 1832 he appeared on the New York Stage

with a comical sketch modeled after a crippled slave that he had observed. He

named his character "Jim Crow."

Daddy

Rice, also known as Jim Crow was the first to create a character

based upon an African American person. It 1832 he appeared on the New York Stage

with a comical sketch modeled after a crippled slave that he had observed. He

named his character "Jim Crow."

Another famous

early minstrel performer was Henry Lane, also known as Master Juba. He

was an African American performer who choreographed dances that mixed plantation

shuffles with Irish clog dance steps. One observer described his act in the

following manner:

Single shuffle, double shuffle, cut and cross cut, snapping his fingers, rolling his eyes, turning in his knees, presenting the back of his legs in front, spinning around on his toes and heels like nothing but the man's finger on the tambourine, dancing with two left legs, two right legs, tow wooden legs, two wire legs, two spring legs—all sorts of legs and no legs—what is this to him? (Marshall and Jean Stearns Jazz Dance, 46.)In 1844, he participated in a series of challenge dances with the White dancer John Diamond. Each tried to out dance the other. There was no clear winner.

In class we will learn some of the dance steps that inspired his movements.

The first group Minstrel act to perform was the Virginia Minstrels. They made their debut in 1843 and advertised themselves as the Ethiopian Delineators.

Later, after 1855, African American performers began to form companies and to imitate the white performers who imitated them.

The minstrel show had a very specific format and structure.The end men make up as follows: First rub a cake of cocoa butter lightly over the face, ears, and neck, then apply a broad streak of carmine to the lips carrying it well beyond the corners of the mouth, then take a little of the prepared burnt cork, moisten it with water, and rub it carefully on the face, ears, neck, and hands being careful to avoid touching the lips. Put on the wig, wipe the palms of the hands clean, and the makeup is completed ("Negro Minstrels," Inside the Minstrel Mask edited by AnneMarie Beane, 1996, p. 124).

Tambo and Bones were named after the instruments that they played, the tambourine and the jaw bone of an ox or cow. These two instruments kept the rhythm for the company of performers. The end men were the nucleus of the minstrel performance. They needed to be excellent singers and were expected to speak and perform with exaggerated "Negro" dialects.

The first group number that most minstrel performed was called the "walkaround." The performers would introduce themselves with a rousing musical number as they walked through the performance space.

The second section was called the Olio. It featured short sketches, stump speeches, comical skits, and variety acts. Often comical characters would speak using malapropisms within political or topical speeches.

Here is a short example of a "Stump Speech."

There hev bin women in the wolrd who hev done suthin'. There wuz the Queen uv Sheba, who was eggselled only by Solomon, and all that surprised her in him wuz that he could support 3,000 womne. Bless Solomon's heart, I'd like to see him do it now! With the size pin-backs and the trains you wear, where cood he find a house bug enuff to hold ‘em? He'd hev to put a wing unto each side uv the temple, and put another story up on top uvv it. And how cood he dress ‘em with muslim at 50 cents a yard, stockin's a dollar a pare, and winter bonnets $20 per one? $20,000 per annum for stockin's! $24,000 per annum for bonnits! Ef he hed lived in these times he'd hev tohev Congress pass several internal revenue bills, to stand sich expenses. ("Speech on Women's Rights," Inside the Minstrel Mask edited by AnneMarie Beane, 1996, p. 137).The third section was an elongated skit or short play, often featuring scenes from plantation life. Word play, punning, and slapstick routines were included in this part of the act. Schticks might include:

Tall Tales

Verbiage about fears and superstitions

Animal Tales (stories about cats, bull frogs, Brer Rabbit, etc)

Banjo Tunes (Like Stephen Foster's Suwanee River, or Camptown Races)

The final section of the Minstrel show featured "flash acts" or spectacle numbers. The show ended with a more up tempo walk around, perhaps a cakewalk number.

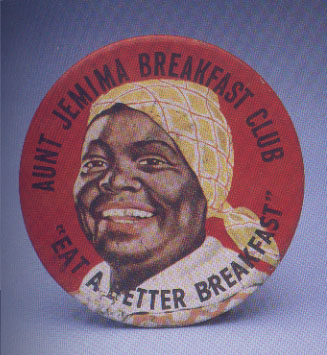

Some of the most common African American stereotypes of the nineteenth century were:

Zip Coon/Urban Dandy

Mammy/Aunt Jemima

Topsy

|

|

|

|

|

|

In its time, minstrel stereotypes did not seem exaggerated to the audiences who attended the shows. In fact, minstrelsy became popular because it purported to show "real" negros as they lived on the plantation. For Northerners who had never experienced Southern culture, it seemed to be a realistic representation.

Perceptions about African Americans were strongly influenced by 19th century concepts of race that were based upon the belief that there was an evolutionary hierarchy of races with Africans at the bottom and Europeans at the top. These theories have since been proven controversial, if not antiquated.

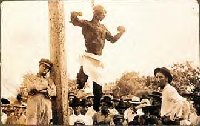

Later

in the century during the Reconstruction era, new stereotypes emerged, most

notably conceptions of African Americans as the Savage Brute. This stereotype

became popular as lynchings became prevalent and Americans looked for

a reasons to justify the escalating violence against Blacks.

Later

in the century during the Reconstruction era, new stereotypes emerged, most

notably conceptions of African Americans as the Savage Brute. This stereotype

became popular as lynchings became prevalent and Americans looked for

a reasons to justify the escalating violence against Blacks.

Minstrelsy did not really end with the popularity of Black Musicals. The variety show format was maintained on the Vaudeville circuit. In class we will be viewing videotape about Vaudeville and discussing the similarities between this entertainment format and early minstrelsy.

Two of the earliest African American musicals were the Creole Burlesque Show (1890 -1897). This entertainment was unique because it featured and all female chorus and was set in an urban environment. The featured performers were Dora Dean and Charles Johnson. They played in New York City and at the Chicago World's Fair.

A woman named Sissieretta Jones founded a company called the Black Patti's Troubadours (1896 to 1915). Jones was known for nurturing and supporting her cast members, especially the child performers. Black Patti was nicknamed after a famous Italian opera singer. Her company included operatic numbers in their repertory.

An important African American musical was A Trip to Coontown featuring the "class act" duo of Bob Cole and William Johnson. The production played on the rooftop garden of a Broadway theater in 1898.

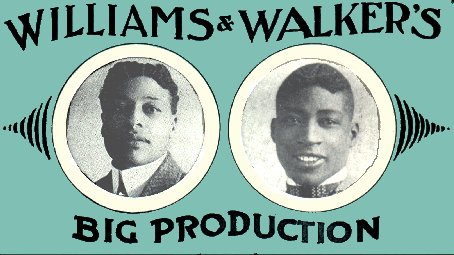

Clorindy or The Origin of the Cakewalk also opened in 1898 and expanded upon dance style known as the cakewalk that was popular in minstrel shows. It was written by the famous poet Paul Laurence Dunbar and the composer William Marion Cook who collaborated on the production in Washington D.C. This production was the first musical that featured the well-known entertainers Bert Williams and George Walker. Their biography is typical of lifestyles of nineteenth century African American performing artists.

George

Walker began his career with a troupe of Black minstrels in Lawrence, Kansas.

Walker traveled extensively with this show, but realized that he needed to strike

out on his own. He performed with medicine shows until he reached San Francisco

where he met Egbert (Bert) Williams. They worked as a vaudeville act for fourteen

dollars a week. They observed other performers as they looked for gimmick for

their own routine, and became fascinated by the "coon" shows done by White performers.

They revamped their own act and began to advertise themselves as "Two Real Coons."

William at first played the straight man and Walker the stooge, but later they

decided that they were better suited for the opposite roles. Eventually Walker

played the dandy and Williams the clown.

George

Walker began his career with a troupe of Black minstrels in Lawrence, Kansas.

Walker traveled extensively with this show, but realized that he needed to strike

out on his own. He performed with medicine shows until he reached San Francisco

where he met Egbert (Bert) Williams. They worked as a vaudeville act for fourteen

dollars a week. They observed other performers as they looked for gimmick for

their own routine, and became fascinated by the "coon" shows done by White performers.

They revamped their own act and began to advertise themselves as "Two Real Coons."

William at first played the straight man and Walker the stooge, but later they

decided that they were better suited for the opposite roles. Eventually Walker

played the dandy and Williams the clown.

Later, a producer brought them to New York and incorporated their act into the Broadway show called The Gold Bug. They were quite successful and soon appeared in the plays The Sons of Ham and In Dahomey. For the play The Sons of Ham, Williams developed a more multi dimensional pathetic character that became his trademark. In Dahomey was the first all Black show to play a major Broadway theater.

For our class we will be reading the musicalIn Dahomey (1902) It is important to note the format and structure of this play is still closely aligned with the minstrelsy tradition. Important featured songs are I'm a Jonah Man, On Emancipation Day, and Evah Darkey is a King. Williams and Walker first developed the idea for this musical when they impersonated African Dahomeans that they had seen at a world's fair in California (1893).

Walker

died in 1911 and Williams went on to perform in The Ziegfield Follies

and other primarily White entertainments. He died in 1922.

Can you find examples of this folkloric material based upon minstrelsy and share them with the class?

How did these stereotypes develop from social fears and economic circumstances of the nineteenth century?

Why did Williams and Walker decide to use stereotypical characters and situations in their performances?

|

[Home]

|

Copyrighted

2001, United States

of America

Anita Gonzalez & Ian Granick